The Systematic Bias of Systems Thinking

How can our systematic perspective and approach bias our systemic understanding and what can we do about it?

I have previously explored the difference between thinking systematically and systemically. A systemic perspective can be useful for understanding a system as a whole. However, since systems are mental constructs, our systemic perspective can be biased by the systematic perspective and approach we use to construct them. This post explores how our systemically constructed systems can be biased, how this might influence our system understanding, how we can reduce our bias, and what we can do about this.

This systematic perspective introduces the potential for bias because there is often more than one way to break reality down into parts, especially when people are involved.

Land as a system

To appreciate how systems are mental constructs, it is useful to explore how we divide land. We can divide the earth into continents, islands and islands, categorise it by different land use, separate it into the flow of water watersheds and claim borders and names for streets, countries, states, territories and properties, tribal or administrative areas, or we can relate to it as an ancestor or as the stories held in place. Some of these partitions are physical, and most are human constructs to a greater or lesser extent. And even this complex divisive exercise is simplified by applying a terrestrial boundary (although we continue to apply similar approaches to the Moon and Mars). Depending on the systematic perspective we set our boundaries and how we dissect the parts, we can construct different systems from the same reality. These different systems we construct can completely change the focus or even the understanding we might reach when we then consider the system as a whole. How might our understanding of water change if we looked at a map of physical water sheds versus the legal allocation of water usage rights?

Recognising the bias we bring to our systems

Therefore, as systems thinkers, we must be aware of how our mindsets and motivations can consciously or unconsciously bias the boundaries, parts, and relationships we define when constructing systems. Even just asking ourselves these simple questions can start to reveal where our bias might influence how we think about systems:

Where else might someone draw the boundaries?

What am I cutting when I dissect my system into parts?

Are there different dimensions someone might use to define the parts of this system?

What does this system look like if we flip the parts and relationships?

Systematic Methodologies

The act of thinking about reality as a system can be subtle or even unconscious. System thinking includes various methodologies, providing a systematic step-by-step process for understanding reality as systems and applying that understanding. I tested several of these through workshops as part of my research into Systems Thinking.

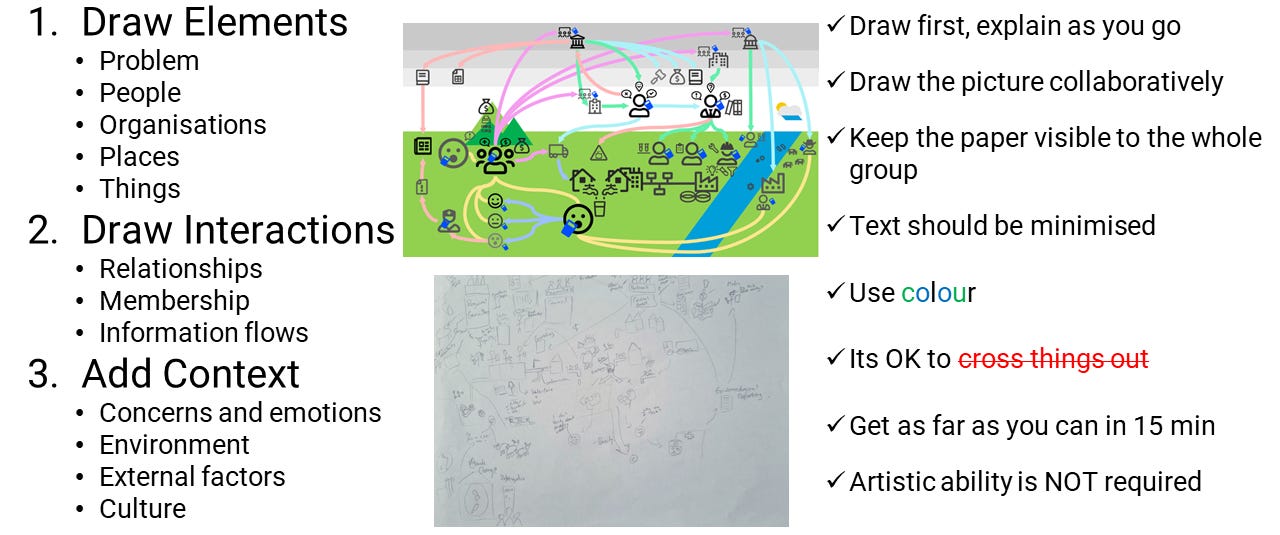

Rich Pictures are a way to represent, organise, and understand reality, using imagery as a more flexible alternative to linear writing. But even something as simple as drawing a picture comes with a set of instructions to systematically step through:

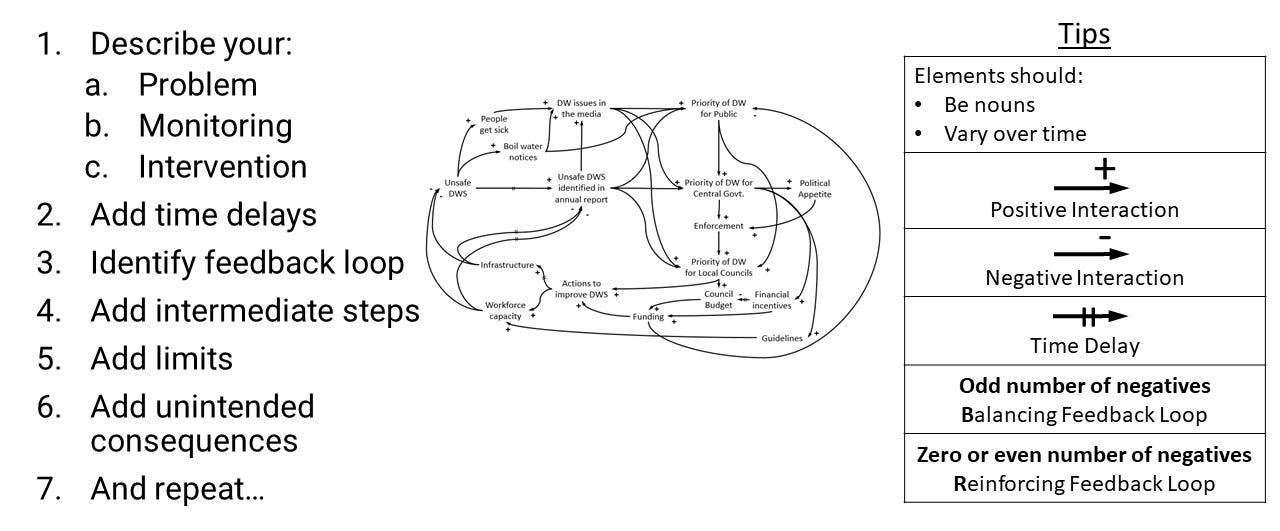

Causal Loop Diagrams are a more structured visual approach to represent things that change in a system: demands, resources, behaviours, or values. They show relationships between them as feedback loops. They also come with various steps and visual language to follow, and they must be balanced to be understandable and functional.

Systems Dynamics Models with mathematical computer simulation and Group Model Building with workshop facilitation processes offer even more sophisticated System Thinking methodologies. While I do not dispute that these methodologies can help us reach a better systemic understanding, we need to be aware of how this understanding is intermediated through systematic processes, often requiring specific skills.

Once again, we should pause and consider:

Why are we using this methodology? Who might it benefit?

How might this methodology influence how we understand reality?

How might this methodology change how we represent reality based on what we can draw? Or measure?

What skills are required to participate in this methodology, and who might we be excluding?

How might each step constrain the following steps? And what chances are there to go back and iterate?

How closely does this methodology need to be followed? Where is there freedom to go with the flow?

Conscious Bias

Appreciating that systems are mental models rather than an objectively true representation of reality is the first step in reducing our bias. Ultimately we will always have biases based on our culture, upbringing, education and lived experience. By making those biases conscious, we can have the humility to take the time to question them and create the space for others to help develop our shared understanding together.

The next post will explore the limits of systems thinking.

Picture Credits